The Avalanches Make Me Want to Visit Australia

Labels: Australia, Music, pop psychology

Born in Banja Luka, Herzegovina, in 1873, little Nestor joined his family who immigrated first to Denmark when he was 18 months and then to Baltimore where they lived for

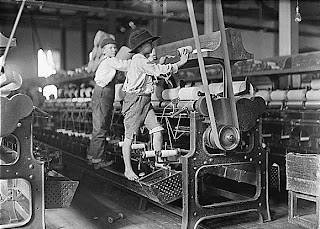

Born in Banja Luka, Herzegovina, in 1873, little Nestor joined his family who immigrated first to Denmark when he was 18 months and then to Baltimore where they lived for three years before his father established a small ale house on Hester Street while young Nestor and his 16 siblings toiled in a button factory where much of his psychological theory evolved through personal toil and triumph. By the age of 14 he rose to a shift manager, overseeing children aged five to eight and was praised by the upper management for his ability to maximize productivity while minimizing complaints, injury and lost limbs. By the age of 16 he published the first of his many pamphlets and soon was much in demand by other factory owners as a speaker on how to get the most out of waif and ragamuffin workers.

three years before his father established a small ale house on Hester Street while young Nestor and his 16 siblings toiled in a button factory where much of his psychological theory evolved through personal toil and triumph. By the age of 14 he rose to a shift manager, overseeing children aged five to eight and was praised by the upper management for his ability to maximize productivity while minimizing complaints, injury and lost limbs. By the age of 16 he published the first of his many pamphlets and soon was much in demand by other factory owners as a speaker on how to get the most out of waif and ragamuffin workers. So impressed were these captains of industry, that they invited him to take their on own children. In 1896 he was appointed the head of collective corrections at the Finger Lakes Institute for Juvenile Mental Hygiene in Mount Kisco, New York. The Institute was funded by a circle of the East Coast's leading millionaires who were eager for Nestor to "fix" their naughty children. One of the unexpected by-products of the Gilded Age was -- despite the advance of wealth, electricity and indoor plumbing -- what these blue bloods considered to be barbaric behavior among their wee ones. In an era where children were meant to be seen and not heard, these decidedly vocal heirs to the New World were sent to Mount

So impressed were these captains of industry, that they invited him to take their on own children. In 1896 he was appointed the head of collective corrections at the Finger Lakes Institute for Juvenile Mental Hygiene in Mount Kisco, New York. The Institute was funded by a circle of the East Coast's leading millionaires who were eager for Nestor to "fix" their naughty children. One of the unexpected by-products of the Gilded Age was -- despite the advance of wealth, electricity and indoor plumbing -- what these blue bloods considered to be barbaric behavior among their wee ones. In an era where children were meant to be seen and not heard, these decidedly vocal heirs to the New World were sent to Mount  Kisco to be muted and corrected. The registry of family names was kept top secret, but as one anonymous nurse observed, "The pedigrees are so prestigious and the children's behavior so heinous that these are clearly the children of the wealthiest of first cousins or worse."

Kisco to be muted and corrected. The registry of family names was kept top secret, but as one anonymous nurse observed, "The pedigrees are so prestigious and the children's behavior so heinous that these are clearly the children of the wealthiest of first cousins or worse." Philadelphia Mainline. From out West, there were the Persistent Pimple Poppers of Pacific Heights. When grouped by location and ailment, Dr. Ben Zvi discovered that he was able to treat these ailments with greater efficiency and speed, closely echoing Henry Ford's assembly line. (He would later try to cure the Ford children's strident anti-Semitism.)

Philadelphia Mainline. From out West, there were the Persistent Pimple Poppers of Pacific Heights. When grouped by location and ailment, Dr. Ben Zvi discovered that he was able to treat these ailments with greater efficiency and speed, closely echoing Henry Ford's assembly line. (He would later try to cure the Ford children's strident anti-Semitism.)

Labels: 19th Century, children's books, pop psychology

After his return from Sacramento, Mr. Sullivan agreed to another session with Dr. Baumgartner.

After his return from Sacramento, Mr. Sullivan agreed to another session with Dr. Baumgartner. "So, vhat animal are you imagining, Mr. Sullivan?"

"So, vhat animal are you imagining, Mr. Sullivan?" "But don't you see a little pussycat?"

"But don't you see a little pussycat?" "Yeah, don't you see me?" said Billy the Blunder Cat.

"Yeah, don't you see me?" said Billy the Blunder Cat. Suddenly the elephant lifted Mr. Sullivan as he let out a girlish giggle.

Suddenly the elephant lifted Mr. Sullivan as he let out a girlish giggle. "Hey, what about me?" Billy whined.

"Hey, what about me?" Billy whined. "Yes, Billy," Dr. Baumgarnter said. "Vhat about you. Vhat was your childhood like?"

"Yes, Billy," Dr. Baumgarnter said. "Vhat about you. Vhat was your childhood like?" Baumgartner returned to Sullivan and approached the elephant. "May I please touch that big, pink trunk?"

Baumgartner returned to Sullivan and approached the elephant. "May I please touch that big, pink trunk?"Labels: architecture, cats, Louis Sullivan, pop psychology

One of the great tragedies for dead artists is that they rarely have a chance to respond to the analysis and critique of their work once they are in the grave. There is still no empirical evidence that the dead haunt the living, but we do know that the future frequently haunts the dead before they go to the grave. Some suspect that it was not a prostitute but news of his paintings selling for seven and eight figures in the 20th and 21st centuries that led Van Gogh to cut off part of his ear.

One of the great tragedies for dead artists is that they rarely have a chance to respond to the analysis and critique of their work once they are in the grave. There is still no empirical evidence that the dead haunt the living, but we do know that the future frequently haunts the dead before they go to the grave. Some suspect that it was not a prostitute but news of his paintings selling for seven and eight figures in the 20th and 21st centuries that led Van Gogh to cut off part of his ear. ssed in Sullivan's interpersonal relationships. A further analysis, including historical factors, would lead us to concentrate on the fascinating anachronism of the figure of Sullivan, an anachronism that (as is so often the case with artists) places him at the peak of his linguistic research during the time of his decline. In short, his professional success was being undermined by a disjunction that can be detected as far back as the late 1880s; right from the beginning of that seventeen-year period that Sullivan indicates as the period of incubation and development of his great crisis."

ssed in Sullivan's interpersonal relationships. A further analysis, including historical factors, would lead us to concentrate on the fascinating anachronism of the figure of Sullivan, an anachronism that (as is so often the case with artists) places him at the peak of his linguistic research during the time of his decline. In short, his professional success was being undermined by a disjunction that can be detected as far back as the late 1880s; right from the beginning of that seventeen-year period that Sullivan indicates as the period of incubation and development of his great crisis." Sullivan felt uneasy from the moment he walked into Baumgartner's overly ornamented office.

Sullivan felt uneasy from the moment he walked into Baumgartner's overly ornamented office. Uncomfortable as the first session had been, Sullivan felt even more ill at ease as the small group circled around him and made him sit in the plush center chair. After nibbling on cookies, they were instructed by Dr. Baumgartner asked them to "check in" as each chronicled the emotional baggage of the past week.

Uncomfortable as the first session had been, Sullivan felt even more ill at ease as the small group circled around him and made him sit in the plush center chair. After nibbling on cookies, they were instructed by Dr. Baumgartner asked them to "check in" as each chronicled the emotional baggage of the past week. hing that you want to share. Some issue that you had to deal with, even if it was something positive."

hing that you want to share. Some issue that you had to deal with, even if it was something positive." Dr. Baumgartner cleared his throat and said, "Okay, let's take a different approach. Mr. Sullivan, let's pretend that your mother and father are in this room. Take a couple of deep breath until you have a clear image of them in your mind's eye. Now what would you say to them, from the depths of your soul, if they were standing right in front of you."

Dr. Baumgartner cleared his throat and said, "Okay, let's take a different approach. Mr. Sullivan, let's pretend that your mother and father are in this room. Take a couple of deep breath until you have a clear image of them in your mind's eye. Now what would you say to them, from the depths of your soul, if they were standing right in front of you."Labels: 1890s, architecture, Chicago, group therapy, Louis Sullivan, pop psychology

There seems to be a happiness conspiracy of sorts out there, and I have to admit that at times I have fallen for it. A couple of my friends have been following the PBS series "This Emotional Life" which concluded with a two hour episode called "Rethinking Happiness" which suggests that people look around in all the wrong places for it or have unrealistic expectations about it.

There seems to be a happiness conspiracy of sorts out there, and I have to admit that at times I have fallen for it. A couple of my friends have been following the PBS series "This Emotional Life" which concluded with a two hour episode called "Rethinking Happiness" which suggests that people look around in all the wrong places for it or have unrealistic expectations about it. ummed out, but I ultimately agree with her that all this happy talk is leaving people numb from real emotions or even having the sanity to see that things are bad and to fight for their rights. Without anger and disatisfaction around segregation, homophobia, sexism, war and a list of countless ills, there also would not have been the movements and activists to take some steps to right these wrongs that still have a long way to go.

ummed out, but I ultimately agree with her that all this happy talk is leaving people numb from real emotions or even having the sanity to see that things are bad and to fight for their rights. Without anger and disatisfaction around segregation, homophobia, sexism, war and a list of countless ills, there also would not have been the movements and activists to take some steps to right these wrongs that still have a long way to go.Labels: Barbara Ehrenreich, books, happy, pop psychology, self help