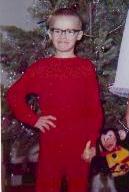

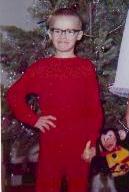

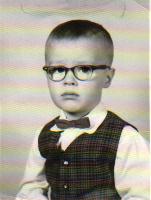

September 1962. I felt under so much pressure. Last year was fun, but I knew kindergarten had been just a lark. My carefree days as a four-year-old helping mommie bake cakes were over. She'd have to fend for herself from now on. This was the real thing. I had to perform. I had to please, especially my grandfather on my mother’s side. He was the one that sent me to that counselor, Dr. Larkin, who tried to figure out why I was at the top of the class one week and at the bottom the next week. Grandpa said that there was only one option for me, and sitting silent was not it.

a lark. My carefree days as a four-year-old helping mommie bake cakes were over. She'd have to fend for herself from now on. This was the real thing. I had to perform. I had to please, especially my grandfather on my mother’s side. He was the one that sent me to that counselor, Dr. Larkin, who tried to figure out why I was at the top of the class one week and at the bottom the next week. Grandpa said that there was only one option for me, and sitting silent was not it.

This was the real thing. My only competition was Gloria S____ who was always barely 2-3 points behind my scores. But she didn’t know phonics, and I’d been reading since I was three and a half, so I really didn’t worry that much about her.

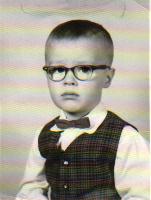

The greatest concern I had, however, was whether or not Johnny M____ would be my friend. He had always been really nice to me on the bus. When other kids made fun of me for being the only kid in kindergarten to wear glasses, he pointed out that glasses were a sign of intelligence and that it would be in their best interest to be nice to me because I could help them cheat on tests. It never occurred to me that Johnny M____ might have been selling me into some form of intellectual slavery. I was too overwhelmed by this older boy whom I desperately wanted to have as my friend, an actual first grader standing up for me, to take time to question his intentions. I couldn’t let his comment stand by itself and had to blurt out, “And I’ve been wearing glasses since I was two and a half.” The moment I said it I worried that I’d gone too far. I was doing what my grandpa told me never to do: brag. But before my snooty words had even had a chance to curdle, Johnny M_____ turned around and, almost sneering, told the other boys, “Yeah…so that means he’s been smart for a LONG time. So you guys better be nice to him.” After he said it, he smacked those lips, like a pair of crab apples glistening in their own sweet syrup.

intelligence and that it would be in their best interest to be nice to me because I could help them cheat on tests. It never occurred to me that Johnny M____ might have been selling me into some form of intellectual slavery. I was too overwhelmed by this older boy whom I desperately wanted to have as my friend, an actual first grader standing up for me, to take time to question his intentions. I couldn’t let his comment stand by itself and had to blurt out, “And I’ve been wearing glasses since I was two and a half.” The moment I said it I worried that I’d gone too far. I was doing what my grandpa told me never to do: brag. But before my snooty words had even had a chance to curdle, Johnny M_____ turned around and, almost sneering, told the other boys, “Yeah…so that means he’s been smart for a LONG time. So you guys better be nice to him.” After he said it, he smacked those lips, like a pair of crab apples glistening in their own sweet syrup.

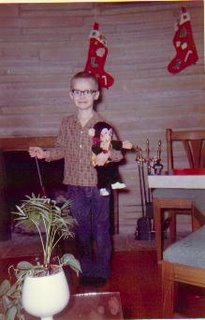

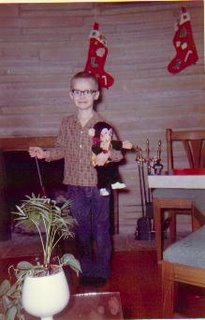

I felt as if a shaken up can of Mountain Dew were exploding inside of my chest. Now I had what I had always wanted, a protector, an older brother. After Johnny turned around, I looked at the closely  cropped dark hair at the back of his neck, the bottom tip of which barely slipped under the top of the collar of his plaid flannel shirt. I wondered if it felt the same as the fake fur on the neck of my stuffed toy monkey that I stroked 200 times each night before I let my mind shut off so I could sleep.

cropped dark hair at the back of his neck, the bottom tip of which barely slipped under the top of the collar of his plaid flannel shirt. I wondered if it felt the same as the fake fur on the neck of my stuffed toy monkey that I stroked 200 times each night before I let my mind shut off so I could sleep.

Even before school started, I had heard that Johnny was being held back a year and would be in my first grade class with Mrs. S______ . I loved the way that sounded, “held back a year,” and I thought of holding back Johnny from whatever I knew he would ultimately run to and no longer be my protector and big brother. I wondered what it would be like to hold Johnny for an entire year, and how long it would take before he would push me away.

In class, I always watched Johnny closely when he was called on to read. I couldn’t even hear what was coming from his mouth, because all I could think about were the lips on his mouth. They were so different from the lips of all of the other boys, so much larger and ablaze with a stronger, more intense color. I searched trough my 72-count Crayola box but could not come up with the perfect color that was on Johnny’s mouth. It certainly wasn’t any shade of red or the pale dusty rose of all the girls’ thin lips. The closest I could come to was raw umber, if only because of the way it sounded. After school, I would pause from playing with my Tonka  Trucks and repeat the words “raw umber,” closing my eyes and thinking of Johnny’s lips and wondering how they got that perfect, moist shade. Did he dip them every morning in some strong strawberry jelly? And then I would think of Johnny’s wounded black bean eyes as they stared at me pleading for help as Mrs. S________ scolded him for his awkward reading.

Trucks and repeat the words “raw umber,” closing my eyes and thinking of Johnny’s lips and wondering how they got that perfect, moist shade. Did he dip them every morning in some strong strawberry jelly? And then I would think of Johnny’s wounded black bean eyes as they stared at me pleading for help as Mrs. S________ scolded him for his awkward reading.

Each day, I longed for recess when Johnny and I pretended to play, when I was actually drilling him until he could memorize the words that he could not iterate from the page. I envied kids who actually could find time to play, when I felt I had so much work to do to help out Johnny and also please my grandfather by being the top in my class. Slowly, his reading was improving, and sometimes we sat with a book during lunch as I helped him with the words. "You're a lots better teacher than Mrs. S________, Gregg. Maybe you should teach our class."

"Yes, perhaps I should," I said. "I'm sure we'd learn much more." One day after school I was thumbing through a copy of Look magazine and saw the headline "Why Johnny Can't Read." I was very upset that my Johnny was being ridiculed in a national magazine and asked my mother if we could write a letter to the editor complaining. Perhaps if I protected him he wouldn't feel the pressure to take care of me and wouldn't mind if I held him back for another year.

Our friendship was reciprocal as he taught me how to shoot hoops and reach the highest rung of the monkey bars, unfathomable tasks that were as natural to him as breathing.

When it happened on February 14, it was one of the few acts in my life I did not plan. I asked Johnny to go behind the piano with me, and then I handed him my crisp glittery Valentine that my grandmother had helped me pick out at Halls flagship store in downtown Kansas City. Johnny hung his head, the way he did whenever he read, his strawberry lips heavy as if filled with sand. He pulled from his pocket a folded card, obviously one retooled from last year. A faded heart cut with pinking shears was glued onto red construction paper. The Mountain Dews spewing inside of me prevented me from even processing the meaning of his prose, each roughly hewn word a jewel I felt I needed hours to digest without fainting as I wrapped my mind around the mishapen letters scrawled in burnt sienna crayon. All I could see was that he’d spelled my name perfectly with all three Gs, followed by a small drawing of a heart with smiles and two tiny bean eyes. It was then I knew I had to find out for sure what I so desperately needed to know -- planning to count to ten before acting, as Johnny stood there with his head hung low. But on the count of six I lost my resolve and planted my first kiss on his forehead. My lips brushed his left cheek on the count of eight. And then, not sure of any numbers now, our lips met, my hand under his chin. His enormous big bean eyes seemed to be bursting with so much excited protein, and I felt so enemic.

My idyl was interupted by a braying, familiar voice. “Hey, what are you two doing?” Gloria S_____, now only 1-2 points behind me in class, stood at the other end of the piano, her hand on her right hip while she stoked her curly blonde mop of hair. “Don’t you have one of those for me?” she asked, puckering up. “No,” I said defiantly, my hand on my left hip. I glanced back at Johnny, his head still hanging, wounded, as his he’d just butchered a page from a basil reader.

“Not even for this,” Gloria S____ asked, holding out a nickel. “Well, okay,” I said, barely planting my lips for a split second on he right cheek. Sylvia T___ then appeared with a dime. And then Tina W______ and Amy G_____ and Tonya R_____. Finally, Big Brenda J_____ entered with two quarters, and I performed the bitter duty of planting my lips on her greasy forehead.

planting my lips for a split second on he right cheek. Sylvia T___ then appeared with a dime. And then Tina W______ and Amy G_____ and Tonya R_____. Finally, Big Brenda J_____ entered with two quarters, and I performed the bitter duty of planting my lips on her greasy forehead.

The news spread within seconds, a line of falling dominos that had reached the sixth grade and my sister’s class who all taunted me on the long bus ride home.

Over our chipped beef and noodle dinner, she shared the story with my parents. Wiping his mouth on a red gingham napkin, my father repeated my sister's final words curtly and without judgment. “Nine girls, Gregg. And did you enjoy yourself?” “Only at the beginning, with Johnny. Now I know that his lips taste like raspberries, not strawberries.” My father patted my head and repeated, “That’s right, and now you know. Be sure to give the girls back their money tomorrow or you’ll come to regret it. Come on now, get your plate to the sink. The Flintstones are on in ten minutes.”

Labels: Memoirs, TV